Following the data

Covid is still with us, but the urgency surrounding it is quickly becoming part of the gentle background music reserved for influenza and other public health problems that are here to stay — music most of us listen to about as carefully as we do the tunes played for us in stores where you push a shopping cart around.

Covid is still with us, but the urgency surrounding it is quickly becoming part of the gentle background music reserved for influenza and other public health problems that are here to stay — music most of us listen to about as carefully as we do the tunes played for us in stores where you push a shopping cart around.

As tempting as it might be to dismiss the pandemic as a bad patch best forgotten, however, there is still a lot to learn from this unpleasant experience. A series of scathing reports published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) at the end of July showcase just how much Canada needs to sort out — now, and sometime in advance of nature’s next inevitable assault on our bodies.

“The world expected more of Canada”, insists the editorial overview introducing this extensive critique, examining everything from systemic demographic inequalities — which consigned some members of the population to far worse health outcomes than others — to the country’s world-class miserliness when it came time to share medicine with other places not fortunate enough to have their own expendable stockpiles.

Modelled after a similar series examining the UK response to covid, the authors represent a wide range of disciplines and perspectives, reflecting the virus’ universal impact on science and society.

“We hope their work informs and advances an independent, comprehensive, and probing review of Canada’s covid-19 response,” concludes the editorial, “to ensure transparency and accountability from governments and health authorities, and to commit leaders to actions that support and sustain preparedness for current and future health needs.”

The legacy of SARS

The BMJ reports lay out the rationale for an independent public inquiry into the pandemic response. Such an inquiry would undoubtedly have to delve into even murkier depths of our collective memory, going back to the original covid crisis: the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak of 2003. While Canada endured fewer than 50 deaths during this initial encounter with the virus — as opposed to some 52,000 two decades later — the response to SARS set the stage for the way things unfolded after 2020.

In fact, governments of the day responded quite commendably to the shock of SARS, creating the Public Health Agency of Canada and various provincial or municipal bodies that should have left us well placed to tackle future disease outbreaks. Unfortunately, the practical result was a highly decentralized system whose various parts did not necessarily play nicely with one another.

PHAC, for example, lacked authority over its provincial counterparts, which subsequently went their own respective ways, with varying degrees of success. More importantly, there was no central body for assembling or distributing information.

“When the pandemic began in early 2020, the Public Health Agency of Canada did not have regulations or finalized agreements with the provinces and territories to clearly outline what public health surveillance information to share and how to share it,” a 2022 Auditor General report revealed. Decision-makers, for their part, were left with a necessarily incomplete picture of what was happening, leading to sometimes confounding or contradictory messages.

According to one of the BMJ reports, something as simple as distinguishing “death with covid” and “death from covid” became a stumbling block for determining how well public policy was faring, sowing seeds of public suspicion. “While these concerns could be overcome with good data documentation, or data and testing standards, inconsistent and changing definitions during the pandemic created public confusion and distrust.”

"Following the science"

In retrospect, as coarse and as crass as the trucker convoy occupation of downtown Ottawa proved to be, this protest could be reliably traced to an overwhelming sense of frustration with events that were turning everyday life upside down, with apparently little coordination and less than satisfying explanations from institutions presumed to be accountable. Even the resounding call from those institutions to “follow the science” wore thin, as a group of University of Ottawa and York University researchers found when they documented the trail of this popular rhetoric across Canada, Australia, and the UK.

“Our results suggest that claims of ‘following the science’ were often used as a form of delegation and protocolisation that justified ineffective or unpopular policies,” they state. “Such claims emerged at the outset of the pandemic when leaders deferred to ‘the science’ to delay and lift public health restrictions and re-appeared when politicians later had to defend controversial decisions.”

To make matters worse, it became increasingly difficult for leaders to cast blame for their actions on science, when a scientific consensus on many aspects of the outbreak proved difficult to achieve. Even now, something as fundamental as the source of the covid outbreak remains hotly debated.

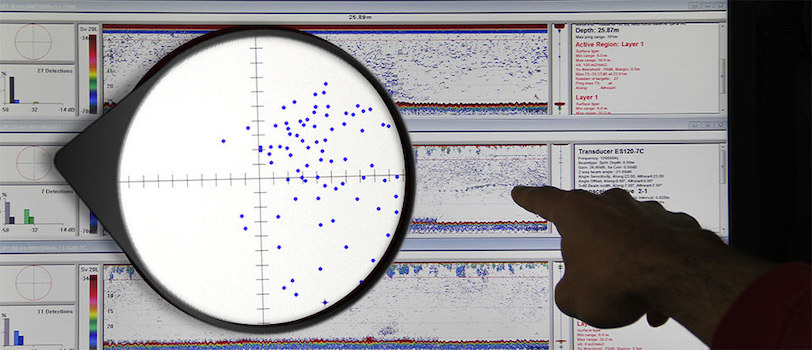

Meanwhile, the BMJ’s extensive critique outlines how much better things would have gone for those leaders if they had instead followed the data. Yet more often than not, there was little data to be had.

“Lack of local data contributed to a lack of understanding of local transmission dynamics and contributed to loss of public trust over time,” says one of the reports. “Collection of data on ethnicity, occupation, and other factors was slow to evolve, and in some places never happened, even though this was clearly related to virus spread.”

That could change, thanks to the massive $196.1 billion block of funding the federal government committed to improving health care across the country over the next 10 years. Some $500 million of that total has been set aside for agencies like the Canada Health Infoway and Canadian Institute for Health Information to hone the data systems that turned out to be so unwieldy at the height of the pandemic.

Yet without a pandemic to motivate that process, the authors of the BMJ reports wonder what will end up getting done. Hence their demand for an inquiry, to determine clearly where problems occurred and even more clearly how they should be addressed.

“One of the benefits of Canada’s federation and decentralised governance in public health is the natural experiments that can occur from which we can identify best practices,” they argue. “To identify them, Canada’s data governance must be overhauled to ensure systematised sharing of data to support better and more coordinated decision making. Public health agencies can rebuild public trust through transparency and inclusion in decision making, data collection, sharing, access, and use. Without reform, the new proposed data infrastructure investments on the part of Canada’s federal government will be wasted.”

R$

| Organizations: | |

| People: | |

| Topics: |

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.