Neurotechnology is here but Canada lacks policy and a regulatory framework to manage it

Danielle Burns is a Nova Scotian writer and researcher focused on ethics, technology and public policy.

Danielle Burns is a Nova Scotian writer and researcher focused on ethics, technology and public policy.

Imagine sitting in a workplace safety seminar, wearing a sleek headband that quietly monitors your brain activity for signs of fatigue or distraction. Now, imagine that the data is sent not only to your employer but also to a third-party analytics firm, where it is stored, analyzed and potentially sold.

This isn’t science fiction. This is neurotechnology. And it is already being tested and sold in Canada.

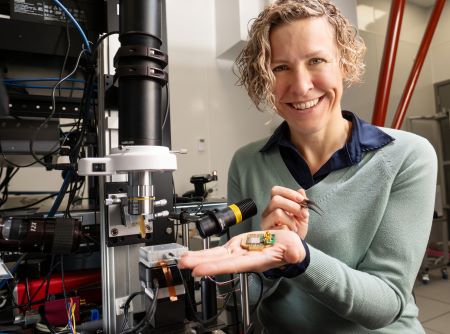

Brain-computer interfaces, EEG (electroencephalogram) headsets and other consumer neurotech products are gaining traction in sectors such as healthcare, education, gaming and workplace management.

These tools are marketed as ways to enhance focus, reduce stress or boost productivity, but they also collect deeply personal information about our mental states. In some cases, they may even influence those states using stimulation or feedback.

Despite this, Canada currently lacks a specific regulatory framework to manage neurotechnology or the neural data it generates.

While the field continues to grow, both in this country and globally, Canada’s policy response has remained tentative and fragmented. This is a significant vulnerability in our research and innovation ecosystem.

As someone who has worked in the policy and research space, I have been following neurotech developments with growing concern.

While Canada is home to leading neuroscientists, ethicists and engineers, we are missing an opportunity to lead in policy and governance. If we want to ensure that neurotechnology benefits the public rather than undermining trust or privacy, we must move forward with purpose.

The technology is already here

Neurotechnology refers to tools that interface with the nervous system. Some are invasive, such as deep brain stimulation implants used to treat epilepsy or Parkinson’s disease. Others are non-invasive and are already in the consumer market. These include EEG wearables, earbuds that detect neural signals, and headsets that claim to improve meditation or enhance focus.

Major tech companies, including Meta and Apple, have filed patents related to the detection of neural signals. In January 2024, Elon Musk’s company Neuralink implanted a chip in a human subject, who later played a video game using only his thoughts.

These devices may still be in the early stages, but the trend is clear: commercial neurotech is no longer hypothetical.

Even with current limitations, the data collected is sensitive. It includes information about attention, fatigue, emotional state and other internal signals. This type of information may not yet reveal complex thoughts but it is still highly personal, and as artificial intelligence continues to improve, it may become far more precise.

Neural data is also already being used in controversial ways. In 2017, pacemaker data was used in a U.S. arson trial. In India, law enforcement has experimented with brain-based lie detection.

If this sounds concerning, it should be. Once neural data exists, it can and likely will be used for purposes beyond its original intent.

Canada is falling behind

Other countries have started to take action. Chile amended its constitution in 2021 to protect neural data and mental integrity. California and Colorado have updated their privacy laws to include neural data. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has also released a draft recommendation on the ethics of neurotechnology, which Canada has the opportunity to support and adopt.

In contrast, Canada’s current position is vague. Neural data is treated as a subset of biometric data under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act.

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner launched consultations on biometric technologies in 2023; however, neural data remains undefined and unregulated in a meaningful way.

Health Canada has also partnered with researchers to create ethical guidance. Dr. Judy Illes, a neuroscientist and director of Neuroethics Canada, has advocated for value-based frameworks rather than rigid regulations.

While this is a thoughtful approach, it risks creating a patchwork of guidelines that lack the legal clarity necessary to protect users or support responsible innovation.

The risks are real

Some industry voices argue that neural data is too crude to worry about. Graeme Moffat, a neuroscientist formerly with Interaxon, told CBC that the signals most consumer devices collect are too noisy to be valuable. However, this perspective overlooks the fact that data, even if imperfect, is still being collected, stored, and sometimes shared.

A 2024 report by the NeuroRights Foundation reviewed privacy policies from 30 neurotech companies. Only one company promised not to share data with third parties. Fewer than half of the users were allowed to delete their data. Most did not encrypt it. The vast majority failed to clearly explain how the data would be used or secured.

Jennifer Chandler, a professor of law at the University of Ottawa, has warned that just because something does not work well does not mean it will not be used or misused. In the absence of clear rules, neural data could be treated as a valuable commercial asset rather than a sensitive expression of personal identity.

What Canada should do

This is a critical moment for Canada to act. A firm policy does not have to restrict innovation; it can support it by providing clear boundaries and fostering public trust.

Canada should:

- Recognize neural data as a unique category of sensitive personal information.

- Update the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act to require explicit consent for the collection and use of neural data.

- Mandate transparency from companies collecting or processing this data, including any third-party access.

- Fund interdisciplinary research into the ethics, social impacts and cultural dimensions of neurotech.

- Engage with global frameworks, including UNESCO’s draft recommendation on neurotech ethics.

These steps are not radical. They are reasonable, achievable and necessary. They would position Canada as a leader in ethical innovation and signal to the international community that we take mental privacy seriously.

A narrow window

We have the opportunity to shape the future of neurotechnology while the field is still in its early stages of development. Waiting until public trust is lost or harm occurs would be both avoidable and costly. Responsible policy is not about predicting the future perfectly; it is about preparing for it thoughtfully.

Canada’s research ecosystem is home to many bright minds, but we need to provide them with a compelling reason to stay. If we want to stop falling behind other countries in emerging technologies, as we have with artificial intelligence and are now seeing with quantum computing and neurotechnology, we need to act now. Waiting five or 10 years will only widen the gap. The talent is here, the infrastructure is here, and the public is ready.

What we need is clear, timely policy leadership to keep pace.

R$

| Organizations: | |

| People: | |

| Topics: |

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.